Exploring two recent cheating incidents and the larger issues at stake

By Josiah Loftin, Aarnav Raamkumaar, and Suhani Thakkar

Staring at the confusing multiple-choice test before them, one student—who has chosen to remain anonymous—realized how utterly unprepared they were. The student knew that their grade was in a precarious place. They weren’t submitting homework or classwork consistently, and bombing a previous exam had caused their grade in the test category to sink.

“I’m not really a fan of being less than others,” they said. “I’d maybe not cheat if everyone was failing.”

In a desperate move, the student slipped the test paper into their sleeve, planning to finish the exam away from the supervised test environment and sneak it back in later. They hoped taking this risk would save their grade.

As the student was not caught, they said they’d do it again under the same circumstances. “I didn’t really suffer much; I just temporarily feared sh*t. Nothing happened. I’m fine,” they said.

Unfortunately, this situation is far from unique at AHS. Across campus, students have increasingly turned to cheating as a last-ditch effort to manage overwhelming academic and social pressures. However, as more students rely on cheating, concerns over academic integrity affect not only peers but also teachers, who are forced to spend extra time monitoring, viewing, and adapting their assignments. Over time, the culture of cheating has made shortcuts both inside and outside of the classroom feel necessary for many students, compromising student growth and learning.

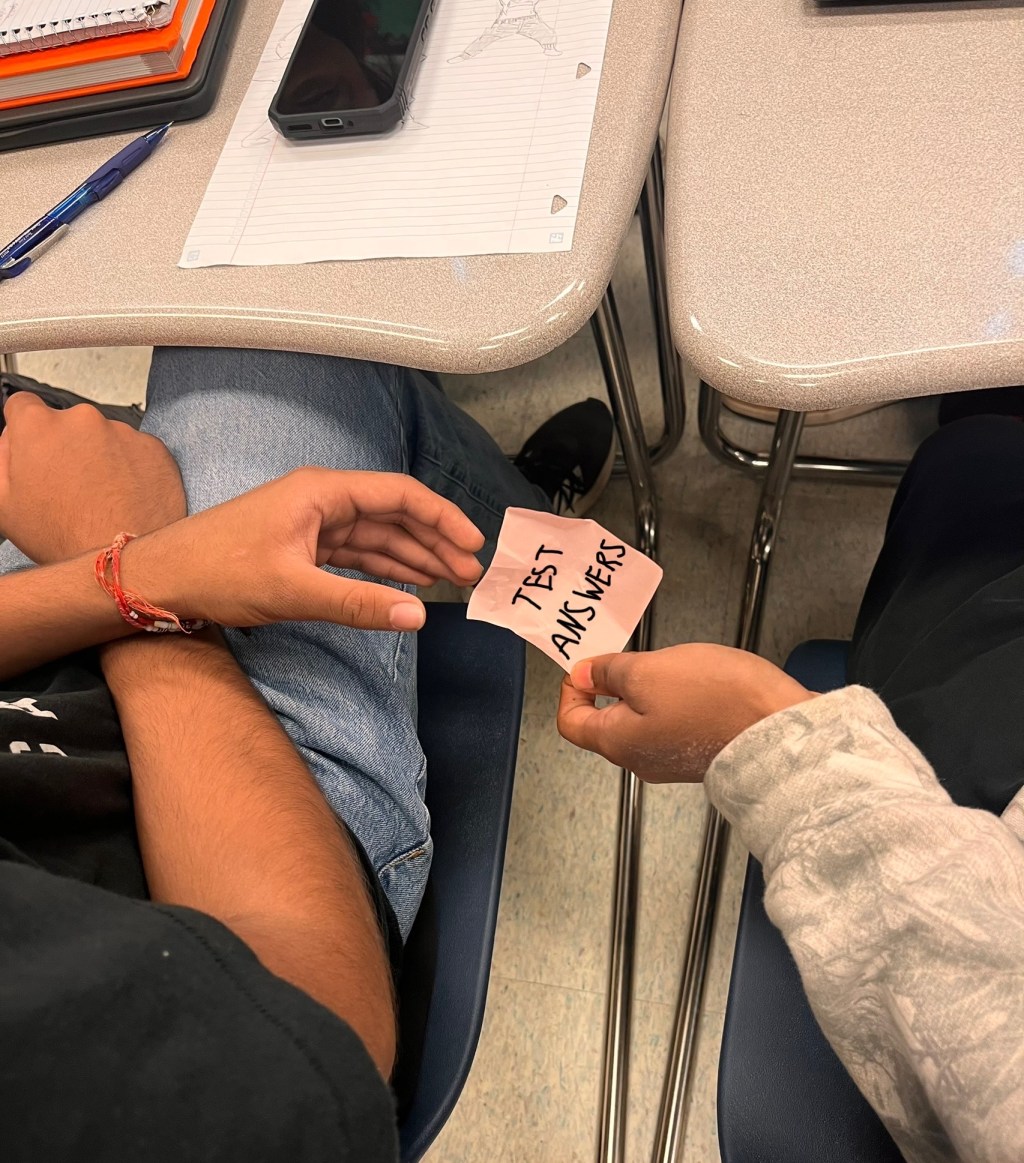

The risk of cheating remains even with traditional paper tests. “Cheating culture is so bad here. Kids don’t really care about learning as much as they care about getting good grades,” said Sahana Reka (11) (Photo Credit: Aarnav Raamkumaar (10)).

Cheating is the Norm

Explaining their decision, the anonymous student said, “For me, it was mainly a last-second thing. It affected my future.” They dismissed moral concerns over academic dishonesty, adding, “In the grand scheme of things, nothing really does matter. Can it be considered wrong if it’s human nature to want to succeed?”

However, not all students are as quick to dismiss ethical concerns. “Cheating culture is so bad here. Kids don’t really care about learning as much as they care about getting good grades,” said Sahana Reka (11).

Fatima Mansoor (11) pointed to the Bay Area as part of the problem. “School, at least in the Bay, is so competitive. Technically a C is average, but if you have a C, it’s [socially] really bad,” she said.

The normalization of cheating at AHS specifically creates pressure to join in, too. Ria Jain (10) said, “I don’t cheat, but I feel like when a lot of people around me are cheating, I’m like, ‘Why am I putting in so much effort when nobody else is?’”

The issue has even extended outside of the classroom, with clubs like Mock Trial experiencing repeated incidents of students submitting AI-generated work. “Mock Trial is something you choose to do,” said one of the captains, Sage Gebrekidan (12). “I find it really disrespectful because when it comes to things that are supposed to be creative and fun, it starts to normalize AI usage in general.”

Gebrekidan noted that this surge in AI usage in all parts of student life marks a larger cultural shift. “We’re starting to prioritize results over being genuine people, which becomes really dangerous; that’s exactly how we start to lack empathy,” she said. “By normalizing things like AI, we are so focused on perfectionism that it starts to make things that are genuinely human seem wrong even when they aren’t and shouldn’t be perceived that way.”

The Struggle to Trust

While students feel academic pressure most visibly, the weight of handling the cheating falls on teachers. AP English Language (APENG) and ELD teacher Mrs. Smith found herself in a difficult situation recently upon discovering approximately half of her class was flagged for AI on an assignment they had around 2 weeks to work on. Students were tasked with critically analyzing how print advertisements manipulate audiences, but the significance of the assignment was undermined when many students turned to AI, leaving Mrs. Smith questioning the value of her efforts.

The ad analysis has been well-established in the APENG curriculum, so it disappointed Mrs. Smith greatly that such an assignment is no longer effective in the face of new technology. “My goal as a teacher is to create students who are critical thinkers and intelligent consumers of the information that they are being bombarded with,” she said. “The reality is that due to the number of ways in which students chose to take shortcuts on this assignment, I will not be able to do this with students again. And even the students whose papers weren’t flagged will not be able to get credit for this assignment because of the choices made by their peers.”

Many students fail to realize that their cheating not only affects themselves but also impacts students around them. As English 9, English 12, Government, and Economics teacher Mr. Rodrigues explained, “When someone cheats, I have to really direct my focus to them. But while I do, there may be many students who actually need my help more. Instead of focusing more of my energy on them, a lot of it is unfairly pushed towards the cheaters.”

With such high flag rates from Turnitin’s AI detector, Mrs. Smith finds herself struggling to know who to trust. “I don’t know if I can trust over half of the students in my class. And the flip side of that is that I also don’t know if I can trust the school-provided resource to help me verify whether the work that is being submitted to me has truly been tampered with.”

But the consequences go beyond the students. Having spent around 40 hours investigating, Mrs. Smith said, “Cheating impacts the teachers too. I got into teaching to help open my students’ minds in my early 20s. When students cheat, I feel like my work is pointless, and it really hurts my heart.”

In turn, the impact of cheating on teachers ultimately comes back to hurt student learning. AP Calculus AB and Accelerated Geometry/Algebra 2-Trigonometry teacher Mr. Stephan said, “We as teachers want to help you, but it gets hard to do that when you use dishonest ways of doing things.”

Challenges and Choices

Cheating is not just an issue at AHS; it is prevalent among high school students across America. According to a 2020 survey conducted by the International Center for Academic Integrity of students at 24 U.S. high schools, an overwhelming 95% of high schoolers have participated in some form of cheating.

This increase in cheating partly stems from increased stress associated with parental expectation. Mrs. Franklin, a psychology teacher, cited expectations at home as a key contributor to cheating. “Pressure from parents and guardians often plays an even bigger role. When parents or guardians actively monitor grades, students feel constant pressure to keep their scores up and avoid disappointing them,” she said.

Students have internalized these external pressures, narrowing the definition of success solely to the pursuit of higher education. “Because of the academic pressure to get into all these good colleges that everybody feels like they’re under, they’re willing to do anything to get it—including being ingenuine when it comes to their clubs and their work in general,” said Gebrekidan.

Unauthorized use of AI tools like ChatGPT has become an increasingly popular method of cheating. Mrs. Smith explained, “The brain is also a muscle. If you don’t exercise it and rely on things like ChatGPT to do your work for you, you are losing those skills and are prone to atrophy” (Photo Credit: Suhani Thakkar (11)).

“When students feel mentally drained or overwhelmed by the amount of work they have, cheating can seem like an easy escape from the pressure,” said Mrs. Franklin. “This reaction is understandable to a certain extent—students often feel like they’re drowning in expectations.”

Apart from external influences, students’ own attitudes also contribute to dishonest behavior. Research cited by The National Institute of Health shows that the cheaters’ moral reasoning skills are weaker than those of non-cheaters. The University of Chicago’s Academic Technology Solutions Center also notes that poor time management commonly leads to desperation, making dishonesty an attractive option.

Dr. Julie, AP Environmental Science and Living Earth teacher, works to keep her students from ever reaching that point, encouraging them to communicate with her instead of cheating. She said, “Day one, I told my kids, ‘If you need something, talk to me. Don’t resort to cheating.’ If you talk to me, we’ll work something out. Don’t ever feel like you’re in a corner with no other options.”

Leave a comment